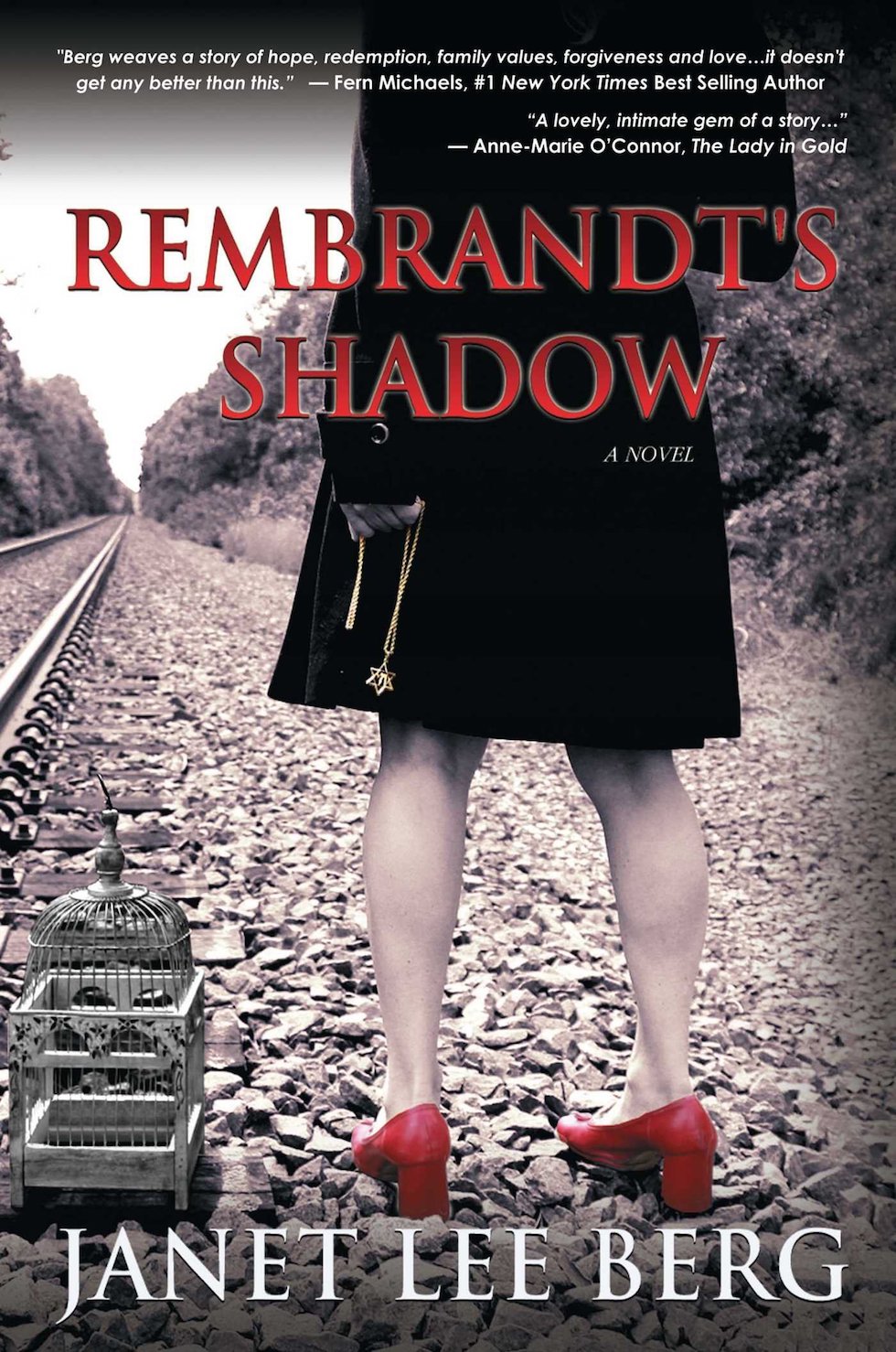

Fiction by Janet Berg

Aug. 20, 2009

Sylvie Beckman, no longer a dreamer, sat in front of the lighted mirror at her makeup table and examined her premature wrinkles. Her magnified eyes curiously returned her stare. She rubbed her eyelids with a cotton ball until they reddened, removing her eye shadow and mascara. The four walls surrounding her got tighter as she thought of the big house in Holland she had lived in growing up, until she was a teen. She remembered how her slight frame had stiffened as she stood in the middle of her bedroom, covering her ears from the air raid blasting through her shuttered window.

All the Jews in the small village had been forced to spend a night at the schoolhouse. Outraged by such humiliation and inconvenience, she stuffed a quilted bed jacket, heavy stockings, and a cashmere hat into the soft leather satchel until it bulged. Numb with excitement, she didn’t dare leave any of her favorite things behind, in case the Germans confiscated their possessions while they were gone. With one more quick glance around her bedroom, she grabbed her rouge and her eyebrow pencil. Satisfied she had everything she couldnt possibly be without, she tugged at the zipper and headed for her bedroom door.

Then, with her hand still on the doorknob, she had remembered the most important thing of all — her solid gold Star of David, which she had kept hidden. Someday this piece would go to her first child. Of course, before the child was born, she’d have to be rescued from her castle and swept away on the white horse by her hero, a man who would be absolutely perfect in every way . . . because once Sylvie had been a dreamer.

Now, many years later, in America, she tried to retrace her steps, to understand why her reflection in the illuminated mirror had become so bitter. The air had been damp that night, an everlasting chill she could not shake, and she had frozen from that moment on and become someone else. Someone who denied any doom that such an excursion could bring upon them. After all, Mama had always promised the Rosenbergs would be safe because . . . because they were different.

Sylvie had kept going back to what she had nervously packed into her satchel . . . how she wished she could bring along her bath salts and her best eau de cologne. But when she was told she wasn’t allowed to bring many of her things, it frightened her; she’d heard of riches-to-rags stories before. She had fought with her mother about her choices, and they played a nasty game of tug-of-war over her prettiest petticoat.

“Hurry,” Sylvie, her mother had said, “It’s not like were going on holiday. . . .”

Mama was right as usual. Because Papa was a prominent art dealer, and the Nazis adored art . . . well, all that scare was for nothing. They had returned home from the schoolhouse unharmed, and none of their things had been touched. Yet their home had lost its comfort; the halls where Father paced seemed longer and Sylvie could almost see Papa’s hair getting whiter by the day. He flicked more cigar ashes than ever before. She had always loved the smell of his cigar until then. Papa had moved much of his artwork during the invasion. She no longer heard him whistling or humming a tune when he came through the front door. Was he afraid, too?

At first Sylvie ignored subtle changes around her on the streets, even though they lost more freedoms. It wasn’t until her own Dutch Theatre, de Hollandsche Schouwburg, where she once imagined herself on the big screen, was turned into a makeshift prison in the Jewish quarter by the Germans that she could no longer pretend. Suddenly the drone of airplanes was overhead and the distant squeal of sirens got too close for comfort. One day Sylvie found herself curled up into a tight ball, petrified that if the closet door opened, she would unravel like Oma’s cylinders of yarn, like Oma, herself, who had a nervenzusammenbruch (a nervous breakdown).

On other days, it was the silence that was worse. She’d peek from behind the heavy curtain, looking at men who walked by in shiny helmets and hobnailed boots below her window. Such a hard sound as they passed, taking her bicycle away. She had always loved that bicycle with the pink basket up front.

Many of the Jewish shops had been closed down and padlocked. Swastikas marked them in devil’s handwriting. Rabbis at the synagogues had to turn over lists of the Jews. Even the church bells no longer tolled. Sylvie wondered what had happened to her Jewish friends . . . Miriam, who lived on Warmoesstraat, and Anna, who lived on Rokensingel. Did they hear fists beating down their front doors in the middle of the night? Did the soldiers burst into their homes and separate them from their mothers and sisters and brothers? Why couldnt their fathers be art dealers, too? Didnt they have anything of value to trade for their lives? The poffertjes mother had prepared on the stovetop, as the spots of sunlight came through the curtains onto the kitchen table, soured in Sylvie’s stomach by noon with more of the horror stories that spread through the neighborhood.

That winter had been unusually cold. The corners of Sylvie’s mouth caved at the sight of her favorite camels-hair overcoat with the black velvet trim. Such a fine fabric, ruined. She could still see the yellow Jewish star, like a badge of courage, sewn onto the front of her double-collar outerwear with the big ivory buttons; the word Jood, Dutch for Jewish, inscribed in black. How ugly the outerwear had suddenly become; its stitching looked painful, fresh as post-surgery. Maybe when the star hardened into a scab, she’d tear it off and watch the coat grow another arm like a starfish.

The only reason the Rosenberg family survived was because of their connection with the Swiss consul, who owned Italian masterpieces Hitler wanted for his collection. But, little by little, Papa was forced into doing a few favors. Goering would walk into Papa’s gallery with a gun in his pocket and discreetly point to a Vermeer. “Ahh, this will be good for Hitler’s birthday; a Jan Steen for the wife; a Nicolaas Maes for a niece. . . .” until the last trade — Rembrandt’s “Portrait of a Man” — in exchange for 25 visas to freedom.

The useful Jews were transported to forced labor camps, and the others . . . babies and children, she dared not think about what happened to the others. Kathryn had told her in English studies once that Joanna heard from Margaret, who heard from someone else, that the Nazis made ovens for incinerating human corpses. Sylvie wondered why people had to make up such far-fetched stories.